“When it became known in March last year that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had used a vessel called the Glomar Explorer to scoop bits of a sunken Soviet submarine from the bottom of the Pacific, a number of scientists in the United States expressed concern that the affair could jeopardise flourishing Soviet-American cooperation in deep sea research. A particular worry was that the Soviet Union might sever ties with the deep sea drilling project (DSDP), a highly successful ocean drilling programme which the National Science Foundation was then endeavouring to turn into an international research enterprise. Ironically, however, the DSDP may turn out to be the chief beneficiary of the CIA’s salvage operations.” — from USA: New career for Glomar Explorer? [Nature, Vol. 264, Dec. 9, 1976]

If you are intrigued by the opening quote above, then you are going to enjoy this story! But note that this blog post is not the full history of Glomar Explorer. Instead, I’ll take you through how the scientific ocean drilling program faced a critical time when an important decision would be made – what would be the next drill ship after Glomar Challenger concluded sailing in 1983? Let’s take a step back and set the stage…

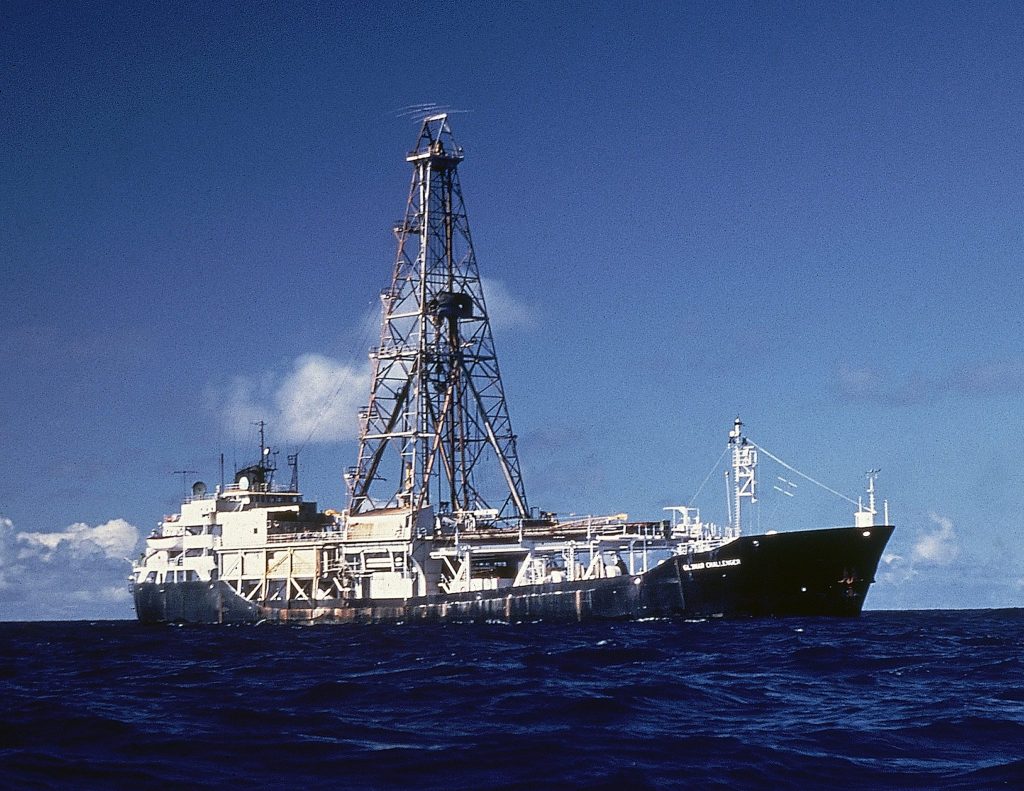

The Open Educational Resource (OER) on Scientific Ocean Drilling: Exploration and Discovery Through Time has pages that describe The start of scientific ocean drilling, Project Mohole, and the original JOIDES Institutions and Deep Sea Drilling Project. The ship Glomar Challenger was a newly-built vessel that began its journey into scientific ocean drilling in 1968. For fifteen years, this ship sailed with scientists, technicians, and crew on 96 expeditions to collect sediments from the ocean floor and the uppermost ocean crust – specifically, it visited 624 sites and collected >97,000 meters of core material. A 30-minute documentary about Glomar Challenger is available on archive.org.

Glomar Challenger concluded its scientific ocean drilling activities in 1983, and at that time was to be retired or would require a overhaul to continue with drilling activities. But even before the official end of the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) with Glomar Challenger, the National Science Foundation was exploring the options available to continue the NSF Ocean Sediment Coring Program.

Glomar Explorer enters the conversation

In addition to Glomar Challenger, there was another vessel in the Global Marine fleet that caught the eye of scientists. It wasn’t a perfect match for the drilling needs, but if conversions were completed on the ship, Glomar Explorer could provide access to even deeper materials and potentially older geologic records.

For a detailed summary about Glomar Explorer, see this article in Smithsonian Magazine or view the documentary Azorian: The Raising of the K-129.

Here is a timeline of events that occurred to determine what would be the next scientific ocean drilling vessel – including, for consideration, Glomar Explorer.

- December 1976 – The National Science Foundation (NSF) announced it was studying the possibility of converting Glomar Explorer into a drilling vessel for use in the 1980’s. [Nature]

- March 1977 – NSF authorized $75,000 for Global Marine Development, Inc., to study the feasibility of converting and operating Glomar Explorer for scientific deep-sea drilling. [EOS]

- February 1980 – The Ocean Margin Drilling Program (OMDP) was formed, an initiative jointly funded by NSF and ten major petroleum companies. The program set drilling objectives to go deeper than existing drill ships. [EOS, Sub-Ocean Drilling (NASA Spinoff)] Glomar Explorer was identified a candidate for scientific ocean drilling, with a major conversion necessary (the addition of safeguards such as blowout protectors, risers, well head controls, etc.). It was projected the ship could begin operations in 1984 and would be able to drill in 4 km of water and extract core from an additional 1,500 meters or more. [EOS]

- October 1981 – The oil industry withdrew its support of the Ocean Margin Drilling Program (OMDP), stated that they were “not willing to support the fiscal 1982 efforts as planned.” This caused much uncertainty for the future of scientific ocean drilling, with Allen M. Shinn, Jr., Director of NSF’s Office of Scientific Ocean Drilling, stating, “I don’t think we [NSF] can continue with the program as it is outlined now.” [EOS]

- November 1981 – The Conference on Scientific Ocean Drilling (COSOD) was held November 16–18 in Austin, TX. At the conclusion of the meeting, the COSOD chairman stated, “Many of these objectives can be accomplished with the presently available drill ship Glomar Challenger, but the extended capabilities of the Glomar Explorer are required to accomplish a large number of other objectives. Thus, it was the unanimous consensus of the conference attendees that Glomar Explorer was clearly the preferable vessel for future scientific ocean drilling.” [EOS] COSOD did not provide scientific goals for the Ocean Margin Drilling Program (OMDP) as OMDP was no more, once the oil industry withdrew its support. [EOS]

- December 1981 – The National Research Council (of the National Academies) Committee on Ocean Margin Drilling reached the same conclusion as COSOD, that Glomar Explorer should be converted to the existing capabilities of Glomar Challenger. [EOS]

- March 1982 – The National Science Board (the policymaking arm of NSF) voted to endorse the efforts to replace Glomar Challenger with Glomar Explorer. [EOS]

The decision

There is so much consensus around moving forward with Glomar Explorer for the next phase of scientific ocean drilling, surely this ship was the one selected, right? Alas, no. Despite COSOD, NSB, and NRC all supporting the selection of Glomar Explorer as the next scientific drilling vessel, in early 1983, the NSF Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Crustal Studies called attention to the point that these groups made their decisions “based only on the scientific merits of drilling and did not look at crustal studies as a whole or look at budget projections.” [EOS] The NSF Advisory Group reached the decision to instead lease a commercial drilling ship.

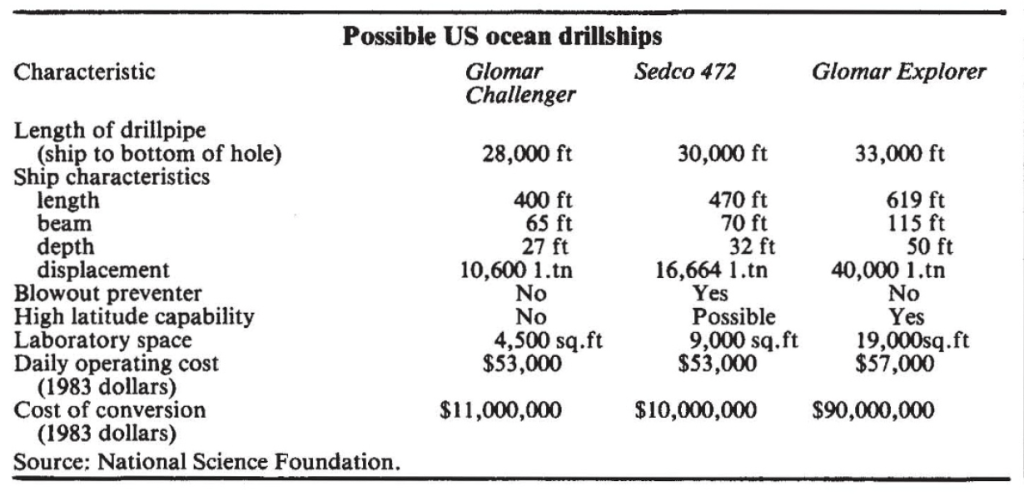

It turns out that the Advisory Group’s decision was well-timed, as a global decline in oil prices made deep-water exploration a non-economical activity for the petroleum industry. This left at least six commercial drillships not in service that could possibly be converted for scientific ocean drilling. The table below is from a Nature News story published in February 1983, noting the physical features and costs of converting the potential drill ships. These numbers were provided to the NSF Advisory Group by Sedco, a Texas company with two drill ships.

In March 1983, JOI (the Joint Oceanographic Institutions, Inc.) designated Texas A&M University as the director of scientific ocean drilling operations. Texas A&M formed an interim team to to implement the NSF Advisory Group recommendations. The interim team was responsible for authoring a request for proposals (RFP) for a drill ship and what the performance criteria would be for a commercial drilling platform. Once a successful bid came in, a formal proposal would made to NSF through JOI. [EOS]

In March 1984, EOS published that there was an Ocean drilling ship chosen for the Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) – Sedco/BP 471, jointly owned by Sedco, Inc., of Dallas, TX, and British Petroleum. The initial contract was for four years and ten one-year options in successive years. Texas A&M University would be in charge of overseeing the ship’s conversation, including the addition of scientific laboratory space. The ship that was the leader in the race to secure a new scientific ocean drilling vessel, Glomar Explorer, was now conclusively not meant to join the scientific ocean drilling community. Instead, after serving as a conventional drill ship for six years, Sedco/BP 471 was converted into a scientific drilling vessel and renamed JOIDES Resolution.

“The drill vessel was named JOIDES Resolution, at the suggestion of Sy Schlanger, who was then chairman of the U.S. Scientific Advisory Committee (USSAC) for JOI. I had proposed the name of another of Captain Cook’s vessels, Endeavor, which I thought would be more representative of the effort to be expended by ODP, but my proposal was turned down because there was another oceanographic vessel of that name currently in operation.” — Kenneth Jinghwa Hsü, Challenger at Sea: A Ship That Revolutionized Earth Science (1992, p. 389)

Moving on from consideration

In 1976, two years after delivering the materials recovered from the Soviet submarine to the U.S. west coast, the U.S. General Services Administration allowed the U.S. Navy to acquire Glomar Explorer and add it to its auxiliary operations. The ship was mothballed in the Naval Reserve Fleet in Suisun Bay, CA, kept a safe distance from other ships due to concerns of residual radiation (The Maritime Executive, 2015).

Fast-forward to November 1996, Global Marine signed a 30-year lease with the U.S. Navy for $1 million pear year and took possession of Glomar Explorer for commercial use in the oil and gas industry. It took 15 months for the ship to be converted from a heavy-lifting vessel to a dynamically positioned deepwater drill ship capable of drilling in water depths of 11,500 feet. The conversation timeline below is compiled from The Maritime Executive (2015) and Offshore Magazine (1998).

- November 1996 – The ship conversation started at the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard (San Francisco, CA). Existing equipment and structures were removed, including the docking legs, the lifting device, and the derrick system.

- February 1997 – The ship then moved on to Cascade General drydock (Portland, OR), and at that time, it was the largest and most complex project this shipyard had ever undertaken. The moon pool was partially filled with 4.5 million pounds of new hull steel to allow for additional storage space for riser and mud systems and an additional moon pool was created to deploy the ROV equipment. The vessel’s electrical, piping, ventilation, and steering systems were also updated.

- September 1997 – The ship was moved to the Atlantic Marine Shipyard (Mobile, AL). The ship was too large to go through the Panama Canal (618 feet in length, 115-foot beam), so the transit from Oregon to Alabama went via the Straits of Magellan around the southern tip of South America. A 2-million-pound capacity derrick with a motion compensator to maintain constant weight on the bit was installed, along with a top drive drilling system. The work was completed here on the ship’s azimuthing thrusters (11 thrusters capable of a combined 35,200 horsepower). In addition, a horizontal drill pipe racking system for 30,000 feet of pipe was installed along with a riser handling system. This was the final location for the ship’s conversion, with the total conversion cost greater than $160 million.

- January 1998 – Glomar Explorer starts its time on the sea as the world’s largest drill ship (at this time), being contracted out to Texaco and Chevron. The now-drill ship spudded its first well in the Gulf of Mexico for Chevron in 7,800 feet of water – at the time, a world record.

After a series of mergers, Glomar Explorer became part of the Transocean fleet and was renamed GSF Explorer. The ship continued with deepwater drilling for the petroleum industry in different regions of the globe, until April 2015 when the vessel was scrapped.

Did you know… in 2006, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) designated Hughes Glomar Explorer a historic mechanical engineering landmark! That same year, the state of Pennsylvania installed a historic marker for Glomar Explorer outside the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia, which is along the Delaware River just north of the site of the Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company in Chester, PA, where Glomar Explorer was constructed.

A key piece of Glomar Explorer history helps the Key Bridge

Shifting the narrative a bit… A horrific maritime accident occurred on March 26, 2024, at 1:28AM (EDT). The container ship Dali had just departed its dock in the Port of Baltimore and was heading south on the Patasco River, Maryland, to begin its journey to Sri Lanka. The ship abruptly lost power, and without navigation controls and a strong river current, the ship crashed into one of the main support piers of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. Six construction workers filling potholes on the bridge that evening on the bridge lost their lives (see this news story and a full-length documentary from NOVA PBS).

Approximately 50,000 of tons of debris now filled the river and stopped ship traffic. The Port of Baltimore is an extremely busy port, processing more cars and farm equipment than any other port in the United States. The Port is also within an overnight drive of one-third of the nation’s population to move items. Suddenly, this hub of maritime commerce came to a halt, as steel and asphalt had to be removed from the channel, as well as the pieces of steel that were now draped across the Dali. Through round-the-clock efforts, the main shipping channel into Baltimore fully reopened 76 days after the incident on June 10, 2024.

One of the pieces of equipment brought in to assist with clearing the debris is the largest crane barge on the East Coast of the United States, Chesapeake 1000. Currently owned by the Donjon Marine Company Inc. Chesapeake 1000 is capable of lifting 1,000 short tons and has been used for large projects such as Hurricane Sandy recovery efforts.

But before the Donjon Marine Company acquired this crane in 1993, it was known as Sun 800 (it could only lift 800 tons in its prior configuration). This heavy derrick barge was built in 1972 and utilized for shipyard construction programs – such as the construction of Glomar Explorer at Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company in Chester, PA! Now Sun 800 did not make the trip to Hawaii for the secret CIA mission in 1974, but it served an essential role in lifting the 630-ton gimbal onto Glomar Explorer during construction.

In summary…

Glomar Explorer has an incredible story. Although this ship is most famously known for its secret CIA mission, she was the focus of quite a bit of discussion and debate in the scientific ocean drilling community. Alas, we’ll never know what we may have discovered from the deep sea if she had been transformed into a drilling vessel with the capacity to retrieve continuous cores.

Glomar Explorer may no longer exist, but there is a phrase that still carries forward the first part of her name and is connected to the submarine recovery mission – check out this short video clip below to learn about the Glomar response (“neither confirm nor deny”). There is also a longer TED Talk on this topic, FOIA v. “Glomar” Response. Yes, Glomar Explorer has left quite a legacy.

This is a great article in a CIA publication titled Ocean Industry from March 1974. See the cover and article that starts on page 32 of this PDF file, ‘Hughes Glomar Explorer’ begins sea tests of mining systems. (*before it was revealed the real purpose of Glomar Explorer...)

LikeLike

[…] example, I previously blogged about the ship Glomar Explorer and its connection to Philadelphia and scientific ocean drill…. When I speak in southeastern Pennsylvania, I always make sure to mention Glomar Explorer – […]

LikeLike

[…] was a big provider of steel for ship construction at the Sun facilities in Chester, PA, such as Glomar Explorer. You can view a series of historic images from GUPPY’s construction and early testing at the […]

LikeLike

[…] posts the connection between Lukens steel and the construction of the hull of JOIDES Resolution, Glomar Explorer, and GUPPY. This blog post will highlight a large object viewable outdoors in the parking lot of […]

LikeLike

[…] G, V. a. P. B. D. (2025, August 19). Glomar Explorer – the ship that almost was a scientific ocean drilling vessel. Journeys of Dr. G. https://journeysofdrg.org/2025/06/18/glomar-explorer/ […]

LikeLike